Doing Science with Our Living Collections: the Case of the Crapemyrtle Bark Scale

One reason we preserve our living collections is to be able to do science with those collections. But sometimes, doing science is also living collections preservation in action. Such is the case with our accessioned crapemyrtle trees (Lagerstroemia spp.) and the associated exotic insect pest crapemyrtle bark scale (CMBS), Acanthococcus lagerstroemiae. CMBS is a new and significant urban forest pest of the southern U.S., and we hope our efforts to protect our collection will scale up to inform long-term sustainable management of this pest and similar insect pests of urban trees.

Adult crapemyrtle bark scale, left scale pierced to confirm active infestation of

live scales. Photo: Jake Hendee

CMBS is a sucking insect pest that has the potential to rapidly transform beautiful, durable, adaptable crapemyrtles into nuisance eyesores in our landscapes. These small insects tap into the sugars moving through the tree’s phloem and excrete that sugar as copious amounts of sticky honeydew. That honeydew, in turn, then molds into a thick coating of black sooty mold up and down the branches, stems, trunks, and adjacent vegetation and surfaces. Heavy infestations of this insect negatively affect the tree’s health, but tree owners who understandably decide they do not want sticky, disgusting, ugly trees are the biggest cause of CMBS-induced tree mortality.

Crapemyrtle: beautiful, durable, adaptable urban tree.

Photo: Hannele Lahti.

Crapemyrtle is a tree that is unique in that it blooms a large part of the summer. As such, it has been planted heavily throughout the southern United States and accounts for a large portion of the range of ecosystem services we enjoy from our urban forests. However, enthusiasm for crapemyrtle planting has waned as contemporary horticultural trends and best practices increasingly recognize the benefits of native species and increased plant diversity. Nonetheless, finding more effective management strategies for this pest would allow us to preserve the ecosystem services provided by our existing crapemyrtles, minimize negative externalities of less sustainable approaches to treating this pest, and apply lessons learned to the management of similar insect pests that impact a wide range of our urban trees, including native favorites.

Dark color on trunks and branches characteristic of

sooty mold. Photo: Jake Hendee

The environmental and financial costs of managing this pest successfully for the long-term are significant. The waxy coating of this scale resists all but the most well-timed applications of insecticides, but we do not yet have precise information about the lifecycle of this pest in our region. The prevailing advice for managing this pest has become using systemic broad-spectrum neonicotinoid insecticides that do effectively kill this pest but that also have significant potential for off-target impacts upon beneficial insects, including ending up in the pollen of this seemingly ever-blooming tree. Additionally, any successful treatment must of course be repeated frequently for continued effectiveness.

Bigeminate lady beetle larva, a native predator of crapemyrtle

bark scale. Photo: Jake Hendee

At Smithsonian Gardens, we have many of the same information needs as urban tree managers across the region about this relatively unknown pest. However, we are unique in our mission as a public garden and museum with living collections. We are in a position to do science and answer some of those information needs. Informed by consultation with partners in the public garden, urban forestry, and academic communities, we have developed a detailed approach to do real world science during the current growing season through systematic monitoring of the lifecycle of this pest on our trees and trials of several low impact management strategies, including augmenting existing native beneficial insect populations. Specific research questions address number and timing of lifecycle stages in this region, scale population numbers on several different groups of treatment trees compared to untreated control groups, residual duration of effectiveness for treatments, and qualitative observations about the role of cultural conditions and beneficial insect populations.

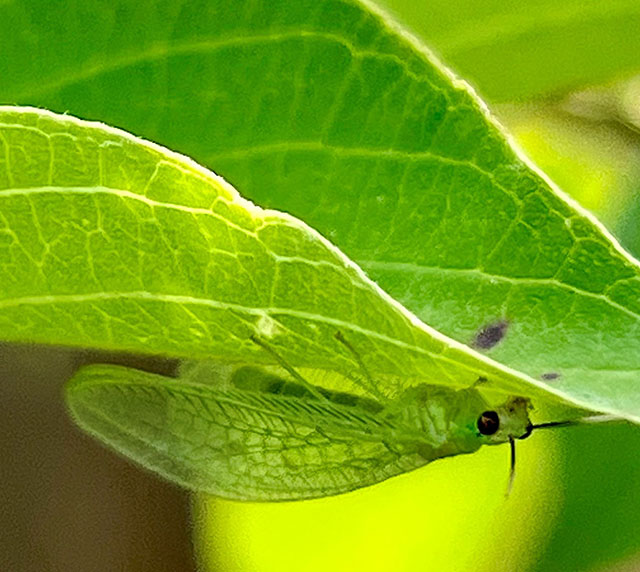

Green lacewing, another native insect predator of crapemyrtle bark scale

and commercially available as a biological control. Photo: Jake Hendee

Lessons from the southern states where this infestation first began indicating that long-term co-existence with this new pest will require growing healthy pest-resistant trees, phasing out a few crapemyrtles to better diversify our urban forests, embracing and protecting beneficial insects, enhancing habitat for our natural populations of beneficial insects. Effective and sustainable low impact management strategies are likely a valuable tool to bridge to that new equilibrium. Lessons learned will apply across the range of scale insects and other insect pests affecting our urban trees and forests.

Flowers of Lagerstroemia indica ‘Natchez’. Photo: Hannele Lahti.

What you can do today to successfully manage crapemyrtle bark scale:

- Pause planting of crapemyrtles. Wait until we know more.

- Focus on keeping trees healthy. Stressed trees encourage proliferation of certain insect pests, including scales.

- Have a replacement plan. Do not panic and remove trees pre-emptively, but do start planning for potential phased replacement of at least some crapemyrtle trees.

- Be cautious with chemical controls. Insecticides also have potential to impact beneficial insects, including pollinators and natural enemies of crapemyrtle bark scale.

- Recognize the role of beneficial insects and other arthropods. A good place to start is adding more flowering and regionally-native plants to your landscape to provide habitat for insect predators and parasitoids of crape myrtle bark scale and other similar pests.

What you can do to make all of your trees more pest-resistant and pest-resilient

- Employ preventive tactics. Select the right tree for the right place. Do you best to get space, soil moisture and drainage, and light conditions right for every new tree.

- Exercise good cultural practices. Plant trees high enough. Mulch trees in wide donuts, not volcanoes to avoid one of our most common and easily preventable tree stressors: stem girdling roots.

- Diversify. Diverse forests have the most redundancy to resist external stresses. Plan and plant for diversity.

- Protect beneficial insects and other arthropods. Most tree pests are naturally managed by other living organisms: predators, parasitoids, and competitors. Recognize the impacts of chemicals applied on these insects too.

- Enhance beneficial insect and other arthropod habitat. Vegetative diversity and complexity, especially flowering and native plants, provide habitat for these natural pest managers.